Apolipoprotein M (ApoM): A Central Regulator of Lipid Homeostasis and Vascular Integrity in Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Systemic Chronic Disease

I. Executive Summary and Introduction:

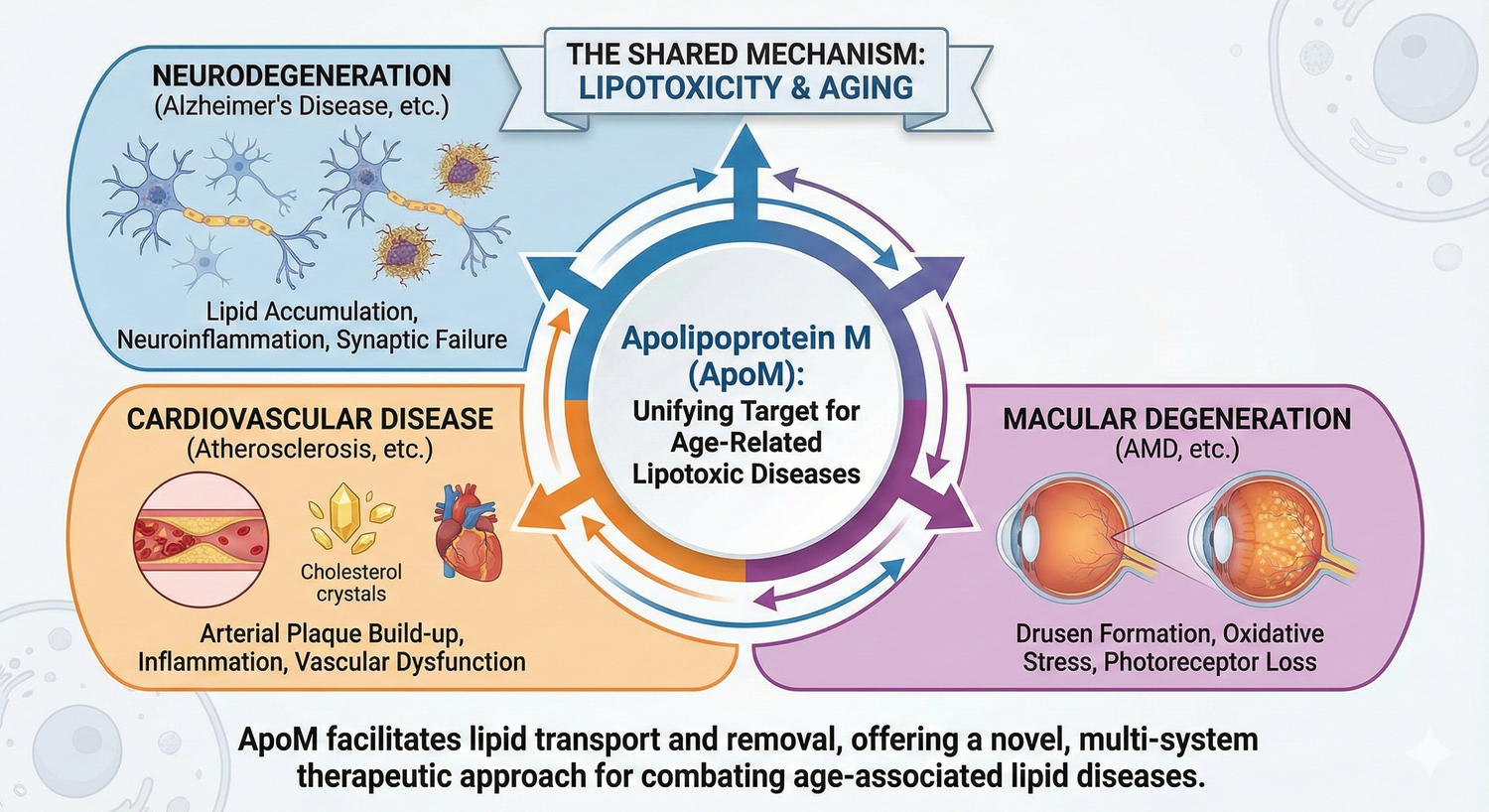

Apolipoprotein M as a Unifying Target for Age-Related Lipotoxic Diseases

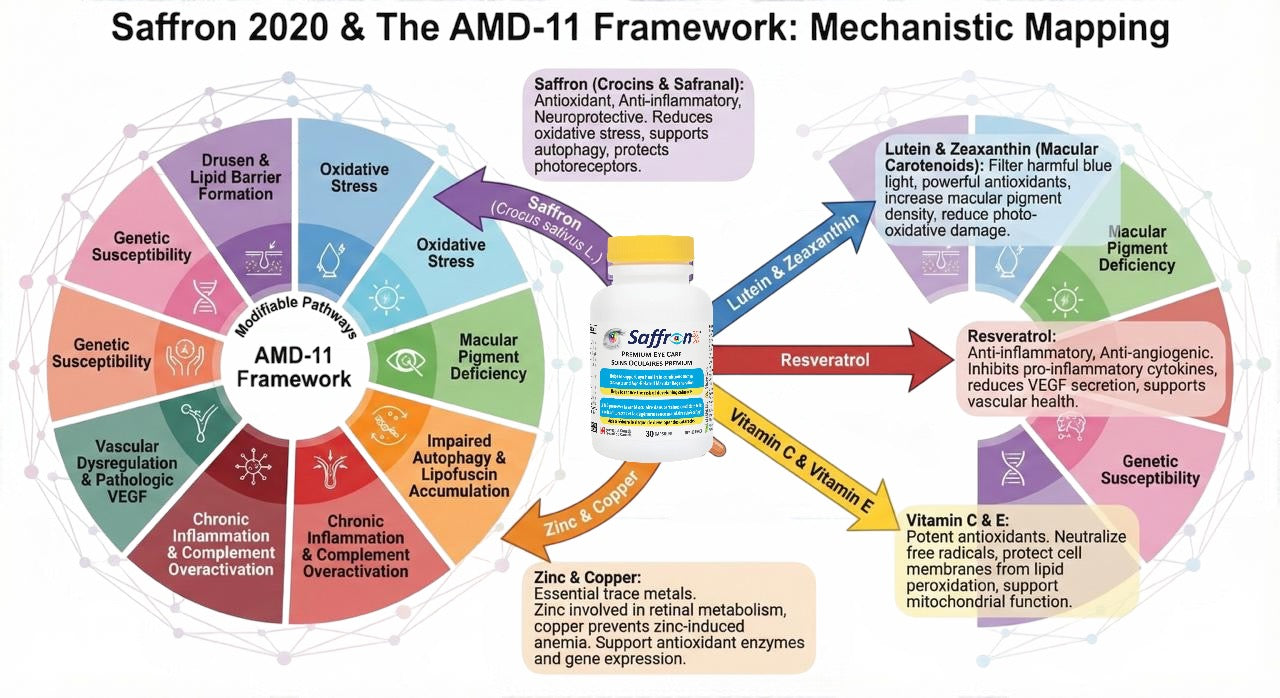

Age-related Macular Degeneration (AMD) stands as the primary cause of severe vision loss in individuals over 50 years of age worldwide.1 The early and intermediate phases of AMD are histopathologically defined by the accumulation of lipoprotein-rich deposits, known as drusen, beneath the Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE).1Progression leads to late-stage forms: Neovascular (Wet) AMD, characterized by abnormal blood vessel growth (Choroidal Neovascularization, CNV), and Geographic Atrophy (Dry AMD), involving extensive RPE and photoreceptor cell death.1

Recent translational research has identified Apolipoprotein M (ApoM) as a crucial molecular link between the ocular lipid pathology of AMD and similar dysfunctional lipid processing observed in systemic diseases, such as cardiovascular disease (CVD).3 ApoM is a plasma protein predominantly associated with High-Density Lipoprotein (HDL).5 Its function extends beyond traditional cholesterol transport, as it serves as the essential chaperone for the bioactive lipid Sphingosine 1-Phosphate (S1P), forming the critical ApoM/S1P complex.7 This complex mediates key protective effects, including anti-atherosclerosis, anti-inflammation, and maintenance of vascular barrier function.5

Systemic analysis provides compelling evidence for ApoM's role in AMD pathogenesis. Studies using human plasma samples reveal that patients diagnosed with AMD exhibit significantly reduced levels of circulating ApoM when compared to age-matched control subjects.1 This systemic deficiency suggests that a failure in the body's general capacity to process and clear harmful lipids, linked to ApoM, directly contributes to the development of ocular lipotoxicity and the subsequent retinal dysfunction characteristic of AMD.3 Therefore, the hypothesis underpinning emerging research is that restoring ApoM levels could re-establish lipid homeostasis and protect retinal function, offering a novel therapeutic target for this debilitating disease.1

II. Molecular Architecture: The ApoM/S1P Complex and Signaling Specificity

A. ApoM Biochemistry and Regulation

ApoM is a 25-kDa plasma apolipoprotein belonging to the lipocalin superfamily.7 Its structure includes a small, internal hydrophobic binding pocket, which is essential for its function, and an $\alpha$-helix formed by hydrophobic signal peptides that anchors the protein to the phospholipid monomolecular layers of HDL particles.6 This association allows ApoM to facilitate the formation of pre-$\beta$-HDL, a structure critical for reverse cholesterol transport.10

The expression and secretion of ApoM are tightly regulated at the transcriptional level by a complex network of factors.5 Key regulators include the nuclear transcription factors farnesoid X receptor (FXR), liver X receptor (LXR), small heterodimer partner (SHP), and liver receptor homolog-1 (LRH-1). Opposing regulatory effects are also exerted by factors such as hepatocyte nuclear factor-1$\alpha$ (HNF-1$\alpha$) and the c-Jun/JunB complex, which competitively bind to sites in the proximal region of the ApoM gene.5

B. S1P Chaperoning and Functional Consequences

The defining function of ApoM is its role as the primary chaperone for S1P in the plasma.7 As an amphipathic molecule, S1P requires a carrier to circulate, and ApoM specifically sequesters S1P within its hydrophobic pocket.7 The resulting ApoM/S1P axis is a powerful signaling system that modulates diverse physiological and pathological processes, including vascular barrier homeostasis, glucose and lipid metabolism, and inflammatory responses.5

S1P mediates its effects through a family of five G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs), termed S1PR1 through S1PR5.7The biological outcome of S1P signaling is highly dependent on the specific S1PR subtype activated and the cell type expressing it.11

C. Differential Receptor Activation in Health and Disease

The strategic importance of ApoM lies in its ability to influence which S1P receptors are activated in different tissues, effectively determining the biological response.

- S1PR1 and Vascular Integrity: S1PR1, widely expressed on endothelial cells, plays a crucial role in maintaining vascular barrier function.7 ApoM-bound S1P provides a tonic stimulus for S1PR1, promoting the formation of endothelial adherens junctions.7 This protective signaling is essential for suppressing pro-angiogenic signals and leakage, both systemically and specifically in the choroid.12

- S1PR3 and RPE Metabolism: Conversely, the beneficial effect of ApoM in clearing harmful lipid deposits in the RPE cells of the eye is dependent on S1P Receptor 3 (S1PR3) signaling.1

The understanding that ApoM is a specific carrier for S1P on HDL is pivotal, as it suggests ApoM is not merely a passive transport vehicle but a molecular delivery system that biases S1P signaling toward specific, protective S1PR pathways.12 The translational implication of this structure is significant, particularly in the context of developing selective therapeutics. If an engineered ApoM analogue, such as ApoM-Fc, is designed to suppress CNV (an S1PR1-mediated effect) while simultaneously relying on S1PR3 activation for RPE lipid clearance, it suggests that the ApoM structure and presentation inherently dictates where and how S1P is delivered to achieve these dual cellular responses.13 This ability to potentially coordinate multiple protective effects across different receptor subtypes is crucial for overcoming the systemic toxicity concerns associated with broad-spectrum S1P receptor agonists.14

III. The Role of ApoM in Age-Related Macular Degeneration Pathogenesis

ApoM’s involvement in AMD is characterized by two distinct, yet related, protective functions: the promotion of RPE lipid clearance in dry AMD and the suppression of pathological neovascularization and vascular leakage in wet AMD.

A. Mechanistic Role in Dry AMD: RPE Lipotoxicity and Catabolism

The primary pathological driver in early and intermediate AMD is the accumulation of cholesterol and other lipids in the RPE, leading to cellular dysfunction and eventual death.3 Research using murine models of dry AMD has conclusively demonstrated that ApoM ameliorates RPE functional deficits and significantly reduces RPE lipid accumulation.1

Crucially, the protective mechanism of the ApoM-S1P complex operates through a novel, cell-autonomous pathway: the stimulation of RPE-specific lysosomal lipid catabolism.1 This finding challenges prior assumptions that ApoM’s benefit was solely derived from promoting reverse cholesterol efflux. The essential nature of this pathway was confirmed through genetic manipulation: when RPE-specific lysosomal function was intentionally knocked out (specifically, lysosomal acid lipase), ApoM treatment failed to provide benefit.1 Furthermore, this RPE-protective mechanism requires S1P binding to ApoM and is specifically dependent on S1PR3 signaling.1

Structural evidence supports the metabolic clearing role. Ultrastructural analyses showed that mice treated with ApoM plasma had significantly fewer lipid droplets in the RPE compared to control mice.1 This observation was associated with enhanced melanosome-lipid droplet interactions, reinforcing the hypothesis that the ApoM-S1P signal drives lysosome-mediated waste disposal within RPE cells, as melanosomes are known to function in concert with the lysosomal system.1 The improved metabolic health translated directly to function, as ApoM plasma transfer also improved rod photoreceptor function in high-fat diet-fed mice.1

B. Role in Neovascular AMD (nAMD)

In nAMD, the ApoM-S1P axis functions as a potent suppressor of angiogenesis and vascular permeability. The circulating ApoM/S1P complex acts through the endothelial S1PR1 receptor to suppress Choroidal Neovascularization (CNV) and associated pathological vascular leakage.13

This anti-angiogenic and anti-inflammatory action is highly effective. ApoM inhibits the expression of proangiogenic factors and chemokines, thereby suppressing the progression of CNV formation.16 The suppressive effect on inflammation by RPE cells is hypothesized to be derived from the activation of the S1P/S1P1 pathway or the inhibition of S1P/S1P2.16 Mechanistically, the suppression of leakage is thought to rely on S1PR1-induced assembly of adherens junctions in choroidal endothelial cells, thereby stabilizing the vascular barrier.12

C. Therapeutic Implications of Dual Pathology Targeting

The analysis reveals that ApoM deficiency is a systemic defect that manifests as a localized, cell-autonomous lipotoxicity in the RPE.1 This understanding suggests that ApoM levels may serve as a crucial systemic biomarker, reflecting general lipid dysregulation that precedes or underlies ocular pathology.18 Consequently, administering ApoM systemically offers a unique therapeutic approach that targets the fundamental metabolic etiology common to both dry and wet AMD.

While current late-stage AMD treatments are localized (e.g., anti-VEGF for wet AMD; complement inhibitors for geographic atrophy 19), ApoM-based therapy offers a potential disease-modifying strategy. By simultaneously activating RPE lysosomal clearance (via S1PR3) and suppressing CNV/leakage (via S1PR1), ApoM modulation could slow or prevent early AMD progression before irreversible damage occurs, offering a significant advancement over current, late-stage intervention strategies.3

IV. Translational Potential: ApoM as a Therapeutic Strategy for AMD

A. Therapeutic Strategy and Preclinical Validation

The research provides a compelling rationale for increasing ApoM levels as a new treatment strategy to slow or block the progression of AMD.3 In preclinical mouse models, researchers demonstrated efficacy using both genetic modification (overexpression of ApoM) and systemic plasma transfer from ApoM-rich mice.1 Both methods resulted in evidence of improved retinal health, reduced cholesterol deposits, and improved function of light-sensing cells.1

A significant advance in translational development is the use of ApoM-Fc, an engineered S1P chaperone protein designed to leverage this pathway.13 Systemic administration of ApoM-Fc demonstrated the ability to attenuate CNV in mouse models to a degree equivalent to anti-VEGF antibody treatment, while also suppressing pathological vascular leakage.13 This result strongly suggests that modulating circulating ApoM-bound S1P acting on endothelial S1PR1 represents a highly promising strategy for treating nAMD.13

B. Current Development Status and Commercialization Pipeline

Commercial development efforts focused on translating ApoM-related mechanisms into clinical use are currently underway.18 Mobius Scientific, a startup company launched from Washington University School of Medicine by senior researchers Rajendra S. Apte and Ali Javaheri, is actively working to develop new approaches for treating or preventing AMD based on harnessing the knowledge of the ApoM pathway.1

Despite the highly promising preclinical data and commercial interest, no clinical trials utilizing ApoM-based treatments in humans have yet begun for AMD.18

C. Mechanisms of ApoM-S1P Signaling in AMD Pathologies

The following synthesis table summarizes the dual mechanism of action of ApoM in age-related macular degeneration.

Mechanisms of ApoM-S1P Signaling in AMD Pathologies

|

AMD Subtype |

Pathological Feature Targeted |

Cellular Mechanism |

Key S1P Receptor |

Therapeutic Outcome |

|

Dry AMD (Geographic Atrophy) |

RPE Lipotoxicity/Drusen Accumulation |

Enhanced RPE-specific Lysosomal Lipid Catabolism (distinct from efflux) |

S1PR3 |

Reduced RPE lipid droplets, improved rod photoreceptor function |

|

Wet AMD (CNV) |

Pathological Angiogenesis/Vascular Leakage |

Cytoskeletal stabilization, suppression of proangiogenic factors (e.g., VEGF) |

S1PR1 |

Attenuated CNV lesion growth, suppressed pathological vascular leakage |

V. ApoM in Cardiovascular Health: Mechanisms of Shared Pathology

The mechanisms governing ApoM's role in the eye share striking similarities with its function in the cardiovascular system, explaining the observed epidemiological links between AMD and heart failure.3

A. Shared Etiology and Systemic Lipid Dysfunction

Like the retina, the heart muscle cells are vulnerable to cholesterol-processing dysfunction. Low ApoM levels disrupt cholesterol metabolism in both the eye and the heart, leading to accumulated lipids, inflammation, and cellular damage.3 Patients with various forms of heart failure have been shown to have reduced circulating ApoM levels, mirroring the observation in AMD patients.9 This established link confirms that ApoM deficiency signals a fundamental systemic failure in healthy cholesterol processing that contributes to major diseases of aging.3

B. Atheroprotection and Vascular Protection via S1PR1

ApoM is a critical component of the "good cholesterol" pathway. It facilitates the formation of pre-$\beta$-HDL and enables the binding of S1P to HDL.10 This ApoM/S1P complex is central to atheroprotection through several mechanisms:

- Anti-inflammation: ApoM+ HDL possesses a more substantial anti-inflammatory effect than ApoM- HDL, largely by modulating macrophage inflammatory responses—a critical process in the development of atherosclerosis.21

- Endothelial Barrier Function: The ApoM-associated HDL-S1P complex mediates the beneficial effects of HDL on the cardiovascular system, including vasodilation, angiogenesis, and protection against ischemia/reperfusion injury.7 By providing tonic stimulation to endothelial S1PR1, the complex promotes the formation of adherens junctions, which are essential for maintaining vascular barrier function and mitigating atherosclerosis.7

The importance of this barrier function is underscored by conditions of acute ApoM deficiency. During the severe acute-phase response of sepsis, plasma ApoM concentrations drastically decrease, resulting in diminished S1P concentrations. This loss of S1PR1 stimulus is believed to contribute to the increased vascular leakage that is a hallmark of sepsis.7

C. Clinical Correlates and Dual Therapeutic Benefit

Clinical studies demonstrate that reduced plasma ApoM levels are independently associated with an increased risk of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events (MACE), particularly in vulnerable cohorts such as non-dialysis patients with Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD).10

The commonality in underlying pathology—impaired lipid metabolism and inflammation—presents a profound translational opportunity. The therapeutic intervention involves raising ApoM levels to improve retinal health.3 Given the shared mechanism, a single, systemic therapeutic approach targeting ApoM (e.g., ApoM-Fc administration or increased ApoM expression) could offer a dual benefit, simultaneously preserving vision and mitigating cardiovascular risk in aging patients.4 This therapeutic efficiency provides a highly compelling case for accelerated clinical development.

VI. ApoM in Other Chronic Systemic Diseases

The ApoM/S1P axis is a fundamental regulator of chronic health, extending its protective effects beyond ocular and cardiovascular systems to influence renal, metabolic, and immune function. The widespread downregulation of ApoM observed across these pathologies suggests that ApoM deficiency serves as a potent marker reflecting the overall decline in an individual's vascular and metabolic homeostasis associated with aging.

A. Chronic Kidney Disease and Diabetic Nephropathy

ApoM is highly expressed in renal proximal tubule cells.6 Research suggests a critical protective role for the ApoM/S1P axis in kidney disease.23

Specifically in Diabetic Nephropathy (DN), the ApoM/S1P-S1P1 axis has been implicated in preserving cellular health. This axis enhances mitochondrial functions and increases the protein levels of Sirtuin 1 (SIRT1), likely through S1P1-selective activation.25 In diabetic mouse models, increased levels of ApoM and S1P were observed in the kidney, potentially serving as a compensatory mechanism to protect the organ against diabetes-induced injury.26 Clinically, these findings suggest that ApoM is a useful biomarker for predicting the progression of DN, and the ApoM/S1P-S1P1 pathway constitutes a novel therapeutic target for prevention or treatment.25 Furthermore, genetic modification studies focusing on ApoM expression and regulation are deemed essential to clarify its role in renal pathology.6

B. Metabolic Syndrome and Diabetes

The ApoM/S1P complex is intrinsically involved in regulating blood glucose and lipid metabolism.5 ApoM, primarily produced in the liver, is thought to play an important role in maintaining the homeostasis of $\beta$-cell function, partly by modulating S1P levels and influencing glucose-stimulated insulin secretion (GSIS).26

The effects of S1P signaling in metabolic syndrome are complex and receptor-dependent; activation of S1PR1 often improves diabetic outcomes, while S1PR2 activation can worsen the condition.28 Genetic variations (polymorphisms) in the ApoM gene have been established in association with lipid disturbances and diabetes, highlighting the protein's direct role in metabolic pathology.6

C. Inflammatory and Immune Disorders

Beyond its role in atherogenesis, ApoM exerts systemic anti-inflammatory functions. The ApoM/S1P axis has been linked to various immune-associated diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis.6 Its influence on inflammation and vascular permeability also means the ApoM/S1P complex is under investigation as a potential biomarker for severe inflammation and sepsis.24

D. Pathological Synthesis Across Systems

The evidence spanning ocular, cardiovascular, and renal pathologies demonstrates a recurring pattern where ApoM/S1P deficiency impairs key cell functions—RPE lipophagy (via S1PR3), endothelial barrier integrity (via S1PR1), and mitochondrial function in renal cells (via S1PR1).1

Table: Known Pathological Roles of the ApoM/S1P Axis Beyond AMD

|

Disease Category |

Specific Condition |

Primary Mechanistic Role |

Translational Importance |

|

Cardiovascular |

Atherosclerosis, Heart Failure, MACE |

S1PR1-mediated endothelial barrier protection; macrophage anti-inflammation |

Low ApoM associated with MACE risk; dual therapy for AMD/CVD |

|

Renal |

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD), Diabetic Nephropathy (DN) |

S1P1-mediated mitochondrial enhancement (SIRT1); renal protection |

Potential biomarker for DN progression; therapeutic target |

|

Metabolic Syndrome |

Type 2 Diabetes |

Regulation of HDL function; modulation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion |

Genetic linkage to lipid and glucose disturbances |

|

Immune/Inflammation |

Rheumatoid Arthritis, Sepsis |

Systemic anti-inflammatory signaling and vascular regulation |

Potential biomarker for severe inflammation and sepsis |

The requirement for ApoM to address different receptor subtypes depending on the target tissue (S1PR3 in RPE, S1PR1 in endothelium/kidney) highlights the intricate nature of its regulatory role. The successful development of ApoM therapeutics must therefore ensure that the systemically delivered agent is able to selectively access and activate the correct S1PR subtype in the specific target tissue to maximize benefits (vascular protection and RPE clearance) while minimizing risks associated with non-selective S1PR activation.13

VII. Conclusions and Future Directions

Apolipoprotein M (ApoM) has emerged as a crucial molecular linchpin linking age-related macular degeneration (AMD) to systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes. The shared underlying pathology is characterized by low circulating ApoM levels, which results in dysfunctional lipid processing, chronic inflammation, and cellular lipotoxicity in vulnerable organs.

In AMD, the mechanism of action is distinctly dual: the ApoM-S1P complex promotes the crucial, cell-autonomous lysosomal catabolism of accumulated lipids in the RPE via S1PR3, while simultaneously suppressing pathological angiogenesis and vascular leakage in the choroid via S1PR1.1 This dual capability presents a highly favorable therapeutic profile, offering a potential preventative strategy for early-stage (dry) AMD and an effective treatment for advanced neovascular (wet) AMD.3

The demonstration that ApoM-Fc, an engineered S1P chaperone, can attenuate CNV equivalently to anti-VEGF agents in preclinical models provides strong evidence for its translational viability.13 Furthermore, the anticipated dual benefit—preserving vision while also mitigating risks for heart failure and cardiovascular events—underscores the potential impact of a successful ApoM therapy on public health.4

The immediate translational challenge involves moving from compelling preclinical success to human validation. Future research must focus on optimizing the delivery and safety of ApoM analogues to ensure sufficient S1PR3 activation in the RPE for lipid clearance, without incurring adverse systemic effects, such as bradycardia, linked to non-selective S1PR activation.13 The initiation of human clinical trials remains the critical next phase to validate the efficacy and safety of targeting ApoM as a foundational approach to managing age-related lipotoxic diseases.

References

- Apte, R. S., et al. (2025). ApoM ameliorates RPE functional deficits in a murine dry AMD-like model. Nature Communications. 1 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12187922/

- Apte, R. S., et al. (2025). Apolipoprotein M Inhibits Angiogenic and Inflammatory Response by Sphingosine 1-Phosphate on Retinal Pigment Epithelium Cells. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science (IOVS). 17https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2691003

- Apte, R. S., et al. (2025). Strategy to prevent age-related macular degeneration identified. Washington University School of Medicine News. 3 https://medicine.washu.edu/news/strategy-to-prevent-age-related-macular-degeneration-identified/

- Apte, R. S., et al. (2025). The ApoM Pathway May Offer New Target for Early AMD Intervention. Retinal Physician. 18 https://www.retinalphysician.com/issues/2025/julyaugust/apom-pathway-may-offer-new-target-for-early-amd-intervention/

- Baldwin, M. A. (2004). Protein identification by mass spectrometry: issues to be considered. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 29 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8487476/

- Bressler, N. M., et al. (1995). Five-year incidence and disappearance of drusen and retinal pigment epithelial abnormalities. Archives of Ophthalmology. 2 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11492580/

- Ding, Y., et al. (2015). Apolipoprotein M and its ligand sphingosine-1-phosphate in health and disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. 27 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25551802/

- Do, H., et al. (2024). Low plasma apolipoprotein M levels are associated with major adverse cardiovascular events in chronic kidney disease. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 10https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/ATVBAHA.124.322367

- Frontiers in Medicine. (2021). The functional role of kidney-derived apoM as well as plasma-derived apoM is far from elucidated. Frontiers in Medicine. 23https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/medicine/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.754490/epub

- Frontini, A., et al. (2024). Novel therapeutic strategy targeting ApoM/S1P in neovascular AMD. Vascular Biology. 13 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC12018641/

- Hla, T., et al. (2019). Apolipoprotein M-bound sphingosine-1-phosphate regulates blood-brain barrier paracellular permeability and transcytosis. eLife. 30 https://elifesciences.org/articles/49405/peer-reviews

- Hla, T., et al. (2019). S1PR1-mediated signaling enhances the efficacy of checkpoint blockade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). 31 https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.1906246117

- Iio, A., et al. (2017). S1P signaling pathways and their implications in metabolic syndrome. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 28 https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/mmr.2015.3658

- Lee, T. Y., et al. (2024). ApoM linked to AMD and heart disease treatment. Ophthalmology Breaking News. 9https://ophthalmologybreakingnews.com/apom-linked-to-amd-and-heart-disease-treatment

- Li, M., et al. (2021). The effects of ApoM on macrophage inflammation in atherosclerosis. Translational Medicine Communications. 21 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC7812182/

- Macular Society. (2023). Second drug for dry AMD becomes available in the US. Macular Society News. 19https://www.macularsociety.org/about/media/news/2023/august/second-drug-for-dry-amd-becomes-available-in-the-us/

- Michaud, C., et al. (2018). S1P regulates HIF-1-dependent cellular responses in RPE cells. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 32 https://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/1/112

- Neuroscience News. (2024). ApoM deficiency disrupts cholesterol metabolism in the eye and heart. Neuroscience News. 4 https://neurosciencenews.com/apom-amd-genetics-29236/

- Park, E. J., et al. (2017). ApoM suppresses the progression of CNV formation by inhibiting the S1P-induced activation of growth factors and chemokines. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science (IOVS). 16https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5796061/

- Qian, H. and Hla, T. (2020). S1P-S1P receptor signaling system in inflammatory processes. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC6939830/

- Raj, M. N. A., et al. (2013). Lipoproteins are multimolecular assemblies composed of lipid and protein bound by noncovalent forces. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science (IOVS). 33https://iovs.arvojournals.org/article.aspx?articleid=2125735

- Saheki, A., et al. (2017). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) and its carriers. Journal of Atherosclerosis and Thrombosis. 8 https://www.jstage.jst.go.jp/article/jat/25/1/25_RV17010/_article

- Science Daily. (2025). ApoM helps eye cells sweep away harmful cholesterol deposits. Science Daily. 20https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/06/250625001724.htm

- Sebag, M., et al. (1991). Image analysis of changes in drusen area. Acta Ophthalmologica. 2https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11492580/

- Takagi, H., et al. (2024). S1P1/5-selective S1P receptor agonist for exudative AMD. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science (IOVS). 14 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC11055896/

- The Ophthalmologist. (2025). ApoM-S1P stimulates RPE's lysosomal system to break down lipids more effectively. The Ophthalmologist. 15 https://theophthalmologist.com/issues/2025/articles/july/slowing-amd-progression

- Wang, L., et al. (2023). ApoM/S1P-S1P1 axis might serve as a novel therapeutic target for preventing the development/progression of diabetic nephropathy. Journal of Advanced Research. 25https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36805561/

- Wang, M., et al. (2014). ApoM in the kidney contributes to the renal S1P content. PLoS One. 26https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4234226/

- Wang, S., et al. (2019). The potential for apoM/S1P as biomarkers for inflammation, sepsis and nephropathy. Biomolecules. 24 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31008738/

- Wang, T. and Zhang, Z. (2022). Apolipoprotein M in diabetic nephropathy. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 22https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2024.1328259/full

- Zhang, S., et al. (2018). The biological function of apolipoprotein M (apoM) and its regulation. Molecular Medicine Reports. 6 https://www.spandidos-publications.com/10.3892/mmr.2015.3658

- Zhang, X., et al. (2023). Sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) in cardiovascular functions. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 11 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10216071/

- Zvonic, S. and Hla, T. (2017). The effects of HDL-S1P on cardiovascular health. Current Opinion in Lipidology. 7https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5756743/

- Zvonic, S., et al. (2022). Aged transgenic APOE mice with targeted replacement of mouse ApoE with human APOE4 develop an AMD-like ocular phenotype. Cells. 34 https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8817708/

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.